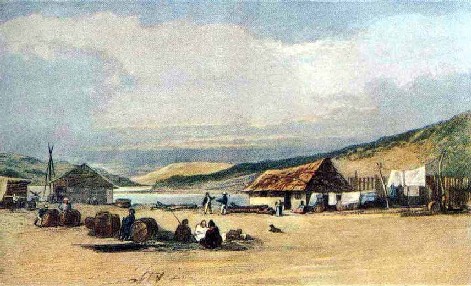

| Twelve months in Wellington / by John Wood (1843)

Chapter 19 |

| Contents: narrative | chapters: 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|

Is, then, New Zealand adapted for colonization? Yes, although its capabilities for supporting an export trade have been ridiculously overrated. The country will rise to importance, but its rise will be slow. It will produce readily every article, at least the staple ones for home consumption. Were a family put down upon any part of its coast, they would soon, with industry, such is the moisture of the climate, raise a subsistence from its poorest soil. This is high praise, and is no more than New Zealand deserves. The seasons are sure, and the country healthy; but it wants both level land to raise and markets whence to convey grain, to enter into competition with the broad corn land of Europe and America.

Let no agriculturist, then, think of visiting these islands with a view of realizing a fortune, and returning to spend it in Great Britain. This is quite chimerical. No one will be benefited by emigration to New Zealand who is unable or unwilling to work for a living. Those who go there must make it their home. We are not speaking of men who go abroad to speculate in trade and commerce, but to the class best adapted for the colonization of New Zealand, and these are the farmer, whose labour is within his household ; the small capitalist, who with his hands upon the plough, can afford to wait until he has a return ; and, lastly, for the poor of the mother-country. The mountains of New Zealand are higher, the morasses deeper, and the forests denser than were those of Britain. It is, in truth, a stubborn country, which only the nerve of a peasant's arm will subdue. The poor man covets a piece of ground, and both Government and the Company should facilitate its possession. A few acres among the mountains is soon, by the labour of his family, transformed into a garden. The ground is his property, and will be his children's when he is no more. He is never wearied in adding to its beauty. The spot is the creation of his own hands, hallowed by a thousand kindly recollections. From this source will yet spring in New Zealand, a numerous yeomanry and a bold contented peasantry. Cottage farms are what the land is calculated for, and they are, doubtless, the best means of subduing a wild hilly country. The New Zealand Company have hitherto done what they could to reverse this picture. But avarice will yet have its reward. In the Wellington settlement country land was sold for £1 per acre. It was afterwards raised to £1.10s. When Nelson was formed, in order more effectually to exclude the very class for which New Zealand is so pre-eminently adapted, or in other words to give the Company less trouble, the section of 150 acres was raised to £300. The proprietors of land in this settlement, even more than in the first, are therefore men who do not intend to benefit the country by cultivation, but themselves by speculation. Let absentees continue to buy square miles of ground : like the clergy reserves in Canada, it lies a clog to the advance of the country and an incubus on the exertions of the industrious. Absentees should be compelled to bear a share in improvements, but at present their agent's reply is, "We have no instructions." The late much maligned Captain Hobson, R.N., acted on a different principle; and, with deference to the collective wisdom of Broad-street, one better adapted to New Zealand. The first, with the country before him, legislated for the mountain territory he saw ; the latter, with only a map upon the table, decreed otherwise. Captain Hobson's measures were practical - the Company's theoretical. The result has been in some measure correspondent. At Auckland, holdings vary from nine to a hundred acres, and the country within three and four miles of the town looks like a well cultivated garden. But here, unfortunately, the high up-set price of land per acre, and the Government mode of selling it, has nearly neutralized the beneficial effect which would otherwise have arisen from small allotments. What, then, do the settlers expect of the New Zealand Company? First, they expect to get the land for which they paid their money in London. Now, such is the nature of the country that they cannot get this without roads. These, therefore, they expect the Company to make - bridle paths will do. But if the settlement is to extend, something must be done to open up the country, otherwise the settlers must remain where they are put down, inactive upon the shores of Port Nicholson. There are other ways in which the settlement may be aided. For instance, we put it to the Company whether they should not, ere this, have taken more decided steps to render flax an article of export? A peculiar method of dressing is required, and until this be discovered the wealth of the soil, like the riches of the deep, must continue useless to the settler. A draughtsman has been paid to make pretty pictures of the country; but would it not more become the names in their Directory to endeavour to get an export for their settlement than to rest its success on the efforts of a painter's brush? Now we would submit that if a portion of the £21,000 lavished on home and colonial establishments had been devoted to the end we have in view, the result would have been far more satisfactory to their own minds. Let them offer rewards commensurate with the object to be attained, and British ingenuity will devise a mode of dressing New Zealand flax. Every vessel from Cook's Straits should bring to England plenty of the raw material, in its natural state, for experimenting upon ; and let the same vessels bring bark from every forest tree to be analyzed by the chemist.

Let the Company shake off their apathy, divest themselves of the idea which has so long possessed them of the extraordinary fertility of New Zealand soil, and do something more than sound the trumpet for their first and principal settlement. Whaling will foster a commercial spirit, and be the means, as capital accumulates, of opening up the country. American and French whalers now fill up with oil almost within sight of the Company's settlement, and that, too, without so much as leaving a dollar behind for supplies with those they are depriving of a profitable employment of labour and capital. We say again to the New Zealand Company, - Roll up your prettily executed maps of "districts open for selection," but which, in too many instances, are inaccessible and worthless for all useful purposes. Instead of raising loans to sink money on the soil, to support a race of gentlemen farmers, for which the country is non-adapted, apply it to make roads and fitting out colonial whalers, and in establishing bay-parties on the coast, so that your settlers may be enabled to engage in an occupation which taking one year with another, has hitherto been found profitable. Give up dazzling the minds of your settlers with the visionary prospect of drawing New Zealand within six weeks of England by a steam communication with the Isthmus of Darien. First aid them in getting the plough into the ground, and that which is now pronounced visionary will in due time become practicable. The question is not, "Can it be done?" but, "Will it pay?" The sea is the highway to your territories. The coast of Cook's Straits is emphatically a "stormy coast." (footnote 1) The nature of the country has compelled you to give out Wellington suburban acres 84 miles from the town, and the country land no less than 112 miles. Both are upon rivers difficult of access to sailing vessels, because the latter cannot always hit the nick of time to enter them. This difficulty a steamer would obviate. Regular communication would induce emigrants not only to go and look at their land, but to settle upon it. A means of sending produce to market would encourage agriculture ; and the discontent, now too prevalent in Wellington, would give place to cheering anticipations of the future. We are aware that the Company have offered a bonus for the introduction of steam into the sister settlement of Nelson ; but if they really wish to see this done, they must do something more.

Footnotes |