| Twelve months in Wellington / by John Wood (1843)

Chapter 12 |

| Contents: narrative | chapters: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

Instead of allowing the New Zealand Company to prove the validity of their titles to the satisfaction of Government, a party in Wellington have been at great pains to complicate the question, and to stir up in the minds of the settlers distrust of a commission appointed by the Crown to adjudicate on this question. The Company's organ charges the Government, among other things, with doing their worst to destroy the validity of the titles upon which the settlers claim possession of their land by stirring up the natives to oppose the occupation of the land by the Company's settlers. To this serious charge the Colonist replies:

To assume that such a deed could ever have been understood by the parties signing it as conveying an absolute right to the purchasers to dispossess them of any or every portion of the land nominally included in its limits, would be to contradict anything that analogy and experience teach of the native character; and to attempt to enforce the literal terms of the deed as against the occupiers of any portion of ground, would be to commit an injustice which no principles of public policy could justify, and which no court of judicature within the British dominions would sanction. In this case, however, who are to blame? They who seek to enforce or they who seek to resist such a claim? We at least cannot condemn the latter." |

But the Gazette preferred Jedburgh justice to the slow operations of the law,

"Measures must be taken to ensure their punishment, or property within the vicinity of the Town will become of no value whatever - a source of trouble instead of profit."We give, without any comment, the following correspondence, originating in a public meeting of the settlers, called on occasion of the dispute referred to, leaving the reader to form his own opinion.

The same number of the Colonist which contained the agent's letter had the following remark:From the Colonist of the 6th September, 1842. "In the first place, then, we retort upon the principal agent of the New Zealand Company the charge of tampering with the native question. Almost from the first moment of our establishment in this place, he has known that there were questions of the gravest character at issue, between himself and the natives, as to the validity of the purchases which he had nominally made. For the adjustment of these questions we are not aware that he has made any efforts. If, in this respect, we are mistaken, let his exertions but be made public, and we will he among the first to acknowledge our error, and to give him the fullest credit for his labours. Of such exertions, however, we have never heard, and we must therefore presume that none have been made. For this seeming apathy in so important a matter, we should have been at a loss to assign a reason, had it not been furnished by Colonel Wakefield himself. At a public meeting, held at the Exchange, we heard the gallant Colonel declare, that he had not taken any great trouble to urge upon Captain Hobson the necessity for the settlement of the native claims ; because, in compliance with the instructions of the Company, he was desirous of keeping the question open, in order that it might be made an instrument in the hands of the Directors for attacking the local government. If this be not tampering with the question, we know not what is. And to add to the impolicy and injustice of such a procedure, it has since appeared that Colonel Wakefield was at that moment authorized by Captain Hobson, to adopt the only really efficacious measures for putting a stop to the disputes thus occasioned, by buying up all unsatisfied native claims! We have asserted what we believe to be the fact, that justice has not been done to the natives. If this is a mistake, it is easy to disprove our assertion. And here, as before, we shall be glad to perceive and acknowledge our error, if it can be shown to be one. But if our view of the case be well founded, our contemporary and the public may rely upon it that any temporary ease, which may be secured by silence, will be dearly purchased, and that every year's delay will complicate the question, and render it of more difficult solution."

Reply of the Company's Agent "To the Editor of the New Zealand Colonist."

"Sir, - The writer of the leading article in the last number of the Colonist, accuses me of charging him with tampering with the native question.

It is true that the Gazette of last week makes this charge against him, but I am at a loss to conceive why I am held accountable for its opinions. I can only say that I knew nothing of the article referred to until I saw it in print. I am further accused of having made 'no efforts for the adjustment of native disputes,' and of having, at a public meeting held at the Exchange, declared 'that I had not taken any great trouble to urge upon Captain Hobson the necessity of the settlement of the native claims, because, in compliance with the instructions of the Company, I was desirous of keeping the question open, in order that it might be made an instrument in the hands of the Directors fur attacking the local government.' This procedure is described as the more impolitic and unjust, 'as it has since appeared that I was at the moment authorized by Captain Hobson to adopt the only really efficient measures for putting a stop to the disputes thus occasioned, by buying up all unsatisfied claims.'

I reply to these grave charges, because they are, unlike some preceding ones, specific; because they affect the character of the Directors of the New Zealand Company ; and, lest my continued silence under accusations contained in the Colonist might lead the public to conclude that I have no answer to them. In respect to the charge of having had the folly to utter at a public meeting the wicked purpose of keeping open the native question in order to furnish grounds of attack un the local government, I declare, most solemnly, that I never at any time made such a statement, or used words which can, by any construction, bear that interpretation ; and I confidently appeal to the persons assembled at the public meeting in question to corroborate my assertion. My instructions from the Directors of the Company, to assist Captain Hobson in any way in my power, and my own acts of deference and submission to his authority, have been too often published to render it necessary for me to say that they are not consistent with the diabolical spirit implied in the speech attributed to me.

To revert to my supposed want of efforts for the adjustment of native disputes. At the public meeting, held soon after Ranghiaieta's attack on the Porirua settlers, I explained, I believe to the satisfaction of all present (as evinced by the manly congratulations of the gentleman who had felt it his duty to question me on the subject), that I had done all in my power, by representations to the authorities and to the New Zealand Company, to remedy the evils complained of. Those representations were made previously to the visit of his Excellency the Governor to Port Nicholson. Upon that occasion I obtained from Captain Hobson, with the assistance of the powerful and enlightened advocacy of the Chief Justice and the Attorney-General, what was considered by many influential settlers, who were acquainted with it, an ample assurance of facilities to put to rest all disputed questions between the settlers and the natives. It was contained in the following letter from his Excellency :-

To W. Wakefield, Esq. Sir, - In order to enable you to fulfil the engagements which the New Zealand Company have entered into with the public, I beg to acquaint you, for your private guidance and information, that the local government will sanction any equitable arrangement you may make to induce those natives, who reside within the limits referred to in the accompanying schedule, to yield up possession of their habitations; but I beg you clearly to understand that no compulsory measures for their removal will be permitted.

I have made this communication private, lest profligate or disaffected persons arriving at the knowledge of such an arrangement might prompt the native to make exorbitant demands.

I have the honour to be, Sir,

Your most obedient servant,

(Signed) W. Hobson

Wellington, 6th September, 1841Although the above letter did not guarantee a proportionate award of land to the Company for any further outlay they might incur in compensating the natives for their locations (as has more than once been asserted to he the case in the columns of the Colonist), I took immediate steps, in conjunction with the local Protector of Aborigines, to obtain possession for the public of the site of the proposed Custom-house in the Te Aro Pah, and other spots occupied by the natives. They had previously expressed themselves willing to remove to their reserves ; but the day after the departure of the Government brig, and four days after the date of Captain Hobson's letter to me, upon my urging them, I was presented with the note of which the following is a copy.

(Translation)

Port Nicholson, 10th September, 1841'Friend Wairarapa, - You ask for a letter from the Governor, that the white man may not drive you from your pahs, or seize your cultivations.

Listen to the word of the Governor: he says, that it is not according to our laws that you should be driven, if you do not agree to go.

This letter is from the Governor.(Signed) Clarke

Protector of the Natives.

'To Wairarapa, Chief of Pipitea.' 'I need hardly say, that all subsequent efforts to effect the removal of the natives from land sold by them in this district, by the same means, have been in vain; but I have sanguine hopes that, by facilities lately opened to me, I shall be enabled, within no long period, to remove the obstructions to the quiet location of settlers on the disputed spots.

I have been reluctantly compelled to extend my communication to this length, and to quote the documents above. I submit them to the public in refutation of the serious charges brought against me in the Colonist.I am, Sir, your obedient humble servant,

W. Wakefield'"

"With regard to the principal object of Colonel Wakefield's letter, the contradiction of our statement as to what he had said at the public meeting referred to, we can do no more than repeat that such was the impression made not merely upon ourselves, but upon others who were present on the occasion. We believe, that by reference to a memorandum made the following day, we shall be able to state almost the precise words employed. The purport of them was certainly what we hare expressed in our paper of Tuesday.And again, in a succeeding number :

We must reluctantly postpone any further comments upon this letter until our next publication."

Circumstances which we could not control prevented us from noticing in our last number the letter of Colonel Wakefield, and an article which appeared in the Gazette of Saturday last. The subject, however, will have lost little of its interest by the delay.The same paper had before truly remarked that -

We are, of course, bound to receive the letter of Colonel Wakefield as a proof that he has no recollection of having made such a statement as that which we charged upon him. But as upon the occasion alluded to we were present as a mere spectator, taking no part in the business of the evening, and only anxious to learn what was said, and what was likely to be done, and as we certainly heard him make that statement, we cannot retract or qualify our charge. We should, however, like to hear Colonel Wakefield's version of what he did say; - though perhaps his memory may not be quite so precise in respect to what his speech did, as it appears to be in respect to what it did not, contain.

The denial of Colonel Wakefield does not, however, stand alone. It is supported by the unhesitating averment of our contemporary - backed by certain solid reasons, showing the utter impossibility of any such declaration having been made. The testimony of our contemporary is one thing - his argument another. We will deal with each separately.In the first place, then, as we know that our contemporary never pledges his veracity to statements of doubtful authenticity - never calls heaven to witness the truth of assertions which he knows would not be credited upon any lower testimony, and would never suppress a truth, or suggest a false-hood, in order to carry his point, we should give the highest possible credence to his denial. But, first, he does not venture to deny having heard the statement ; and, secondly, if he did - that he did not hear it, cannot destroy the impression made upon us by the fact that we did. We remain, consequently, unconvinced, even by the peculiar fervor and solemnity of our contemporary's assertion of the falsehood of our charge.

In the second place, however, we are informed that the declaration alluded to was 'so remarkable, so astounding,' that it must have been heard, and, we presume, remembered. Of all reasons to be urged in support of our contemporary's contradiction, this is the most extraordinary. The only thing in the slightest degree remarkable in the matter was, that Colonel Wakefield should have, to that extent, departed from his habitual taciturnity. But certainly, among the entire audience, there was not one person who would be astounded by hearing that Colonel Wakefield had been endeavouring to aid the Company in England, and the violent party in Port Nicholson, in their endeavours to procure the removal of Captain Hobson. Nor, we venture to affirm, would any one have been, we will not say astounded, but even surprised, by hearing that this was to be done by turning to account the unsettled state of the questions between the natives and the colonists. We believe it to have been so perfectly understood, that the Company's supporters in this place were, by all means, to weaken the position of Captain Hobson, that the enunciation of this particular mode of attack would excite no especial notice. It might be remarked upon as ingenious; but, assuredly, no one - not even our contemporary - would dream of being astounded by it.

Perhaps, as tending to the elucidation of this question, Colonel Wakefield would publish the extract which he read from one of his despatches to the Directors, referring to this subject. Probably we shall have the whole printed in England, but this may lie too late to effect the purpose for which we now desire its production.

And this brings us to a consideration of the concluding portion of Colonel Wakefield's letter, in which he alleges that he has failed in his attempts to remove the natives of Port Nicholson from the land which they have sold, in consequence of a letter written by Mr. Clarke, the Protector of Aborigines, in contravention of the arrangement professed to have been made by the Governor. We beg Colonel Wakefield's pardon. He does not allege this. But this, whether rightly or wrongly we do not pretend to decide, is the only meaning we can affix to his letter. Possibly the involuntary error into which we have fallen in this instance, which we are able to correct from the circumstance of the letter being before us, may explain the cause of the difference which exists between ourselves and him on the previous topic. However this may be, we must comment upon the letter as though our interpretation were correct.

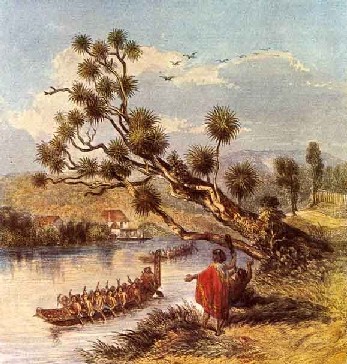

Upon this subject then we have to remark, that the natives of Te Aro, the only place to which Colonel Wakefield specifically refers, deny that they were parties to any sale to him; that when Captain Hobson, in company with Mr. Halswell, and we believe also with Colonel Wakefield, visited that Pah, in order to persuade them to abandon it, the natives unanimously declared that nothing but absolute force should make them relinquish its possession; and that the letter written by Mr. Clarke is nothing more than a simple statement of an undeniable principle of English law, at least as old as Magna Charta, which it was his unquestionable duty to communicate to them if the question were asked. We presume our contemporary will hardly, in writing, deny the validity of Mr. Clark's law upon this point. He will hardly affirm, that it is according to English law that any person, even though a Maori, should be driven from his property. Still less, we imagine, will he dispute the obligation imposed upon Mr. Clarke, in his office of Protector of the Aborigines, to inform the natives that they were not beyond the pale nor beneath the protection of the English law ; and that the jealous securities with which that law has fenced round the possessions even of the poorest might be claimed by them from the very moment their country was proclaimed a portion of the widening dominions of the British empire.

We cannot quite acquit Colonel Wakefield of having employed expressions which, however designed, certainly appear calculated to mislead. Does he mean that the Natives of Te Aro have sold him their land? That would appear to be a necessary inference from the terms he has used; but we can hardly imagine him to intend to make such an assertion. If that is his meaning, we can only say that the natives most firmly deny that they were parties to any sale, and that we have never heard of any transactions in which they took a part, having even the semblance of a valid sale. If he does not mean to refer to the sale of Te Aro, then we should like to know the circumstances under which he has made any 'efforts to effect the removal of the Natives from land sold by them,' and has failed in consequence of anything that could be traced directly or indirectly to the letter of Mr. Clarke."

"as the foundation of the assertion of British sovereignty in this island is the recognition of the native titles to land, it is obvious that the Government cannot interfere summarily to dispossess the natives, or to enable the European settlers to take possession of land nominally conceded to them. When once peaceable possession has been obtained, under such circumstances as would deprive an English landholder of his right to proceed summarily, then the occupant of land may fairly expect from the Government authorities the same protection against unlawful aggression on the part of the natives that he would be entitled to claim against one of his own countrymen. In such case, if the title of the native be valid, he must, we would submit, be required to assert it in a court of law, through the instrumentality of the Protector of the Aborigines; or, if this should be deemed inexpedient, as we imagine would be the case, his title must be extinguished by purchase, either by the individual claimant of land, or by the agent of the New Zealand Company. We believe the latter would lie, in almost all cases, the preferable course, since the former could hardly fail to create a feeling of insecurity dangerous in the highest degree to the progress of the community."These plain truths were unpalatable to the Gazette, and a charge of sacrificing the interest of Port Nicholson is brought against the Colonist, to which that paper replies, -

"We believe that danger lies in the existence of injustice, not in its being proclaimed; and that to remove the evil complained of not to stifle the voice of complaint, is the true source of safety. We do not think that justice has been done to the natives, and we have never conversed with any one who asserted that it had."Shortly after this was written, the Company's agent shook off his lethargy and departed for the seat of Government, having for the object of his, visit the settlement of this question, on which occasion the Colonist remarked -

"The result of this journey may be of the very utmost importance to this settlement. Difficulties that might otherwise press upon us for years may be at once removed, and disheartening doubts and harassing delays may be altogether prevented. We have never had any fears as to the ultimate adjustment of all the questions that have arisen or may arise between the settlers and the natives, upon terms which should be just to the New Zealander, but at the same time should give to the colonists the lands they have purchased. But, as Government would neither violate the rules, nor anticipate the decision of the law, we did sometimes fear that the inevitable imperfections in the titles acquired by Colonel Wakefield might be felt as a very serious obstacle to our progress. These imperfections may now be remedied, and the work, which was necessarily left incomplete in the first instance, may, under the auspices of the Government, and with the aid of the Commissioner, be brought to a final and satisfactory adjustment."