The Land of Tara and they who settled it, by Elsdon Best

Takitimu, from Eastern Polynesia, arrives at the Great harbour of Tara. p. 28

Now, after the above fight, a long time afterwards, 'Takitimu' (a vessel commanded by Tamatea) arrived and lay there for while, having come from Hokianga and Muriwhenua, in the Nga-Puhi region (North New Zealand). Enough ; for the sojourn of Tamatea-ariki has already been related by me, and his going to the South Island, when Tamatea, Te Rongo-patahi, Kohupara, Puhi-whanake, Kaewa and Maahu went, the folk of Ngati-Waitaha clan were numerous. When 'Takitimu' had gone on, then Mapouriki,Te Hoeroa and Te Kahawai arrived, Whatonga had sent them to visit his people, to ascertain how they were getting on.

Tara and Tautoki separate the Boundaries of their Lands (pp. 28-29)

About this period Tautoki and his people moved away and settled at Wai-rarapa, while Tara and his folk became the permanent residents of Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara and as far as Wai-rarapa. But Tautoki occupied Wai-rarapa only, extending toward Tamaki (Wood-ville), and toward Te Rerenga-o-Mahuru, which bounded his area of occupation. His boundary then cut across to the Akitio stream, followed that down to the great ocean, then along the beach southward to the Great Harbour of Tara, then ran up the Heretaunga (Hutt) river to its head, then on to Te Rere-a-Mahanga (near Te Toko-o-Houmeu, on the range west of Featherston), thence to Nga-Whakatatara and as far as Kauwhanga (a hill or peak near the Manawatu Gorge). It then ran down to the Manawa-tu, struck inland to Kai-mokopuna (a mokopeke ? named from a lizard), where the boundary closed. All these lands belonged to Tautoki and his elder brother aud their descendants, even down to this generation the māna of their descendants remains good over such lands as they retained. Some portions were handed over to other peoples by the brothers and by their grandchildren and descendants.

Now the boundary of the western portion ran up the Heretaunga river to its head, thence it connected with Te Rere-a-Mahanga, then struck westward to Taumata-o-Karae, then ran into the head of the Otaki river, and ran down as far as the western ocean, crossed over to Kapiti, ran thence to Mana, thence to Te Rimurapa (Sinclair Head), thence to the headland of Para-ngarehu (Pencarrow Head), thence along tho sea beach us far as the mouth of Heretaunga (Hutt river). This region was retained by Tara, his offspring and people, only.

Ngati-Mamoe Refugees settle at Sinclair Head. (p.29)

It was while Tara was yet living that Ngati-Mamoe arrived and settled at the Great Harbour of Tara. He handed over to them the lands of Pahua (Karori and lands southward of it) as far as the ocean, thence to Te Rimurapa (Sinclair Head), and as far as Wai-pahihi (one of the streams flowing into Cook Straits), the mouth of which faces Arapawa (South Island). Thence the boundary ran up that stream and struck the breast of Te Wharangi, a ridge that extends to the Porirua district, thence it ran to the eastern side of Te Wharangi, descended to the Waikohu stream and eastwards toward the Great Harbour of Tara, as far as the head of that stream, then struck off toward the south, ascended the ridge of Te Kopahou, ran along the top of the ridge to the salt-water sea at the south side of Te Hapua (Te Hapua o Rongomai), on the western side of the place called Island Bay; that place is Te Hapua. That completes the bounds of the lands handed over to Ngati-Mamoe at that time. At the time when Ngati-Mamoe migrated to Arapawa (South Island) and abandoned the lands, all of them came again into the possession of Ngai-Tara.

Here ends the story of the exploration of Wellington Harbour by Tara and his followers, of their settlement on its shores, and of some subsequent events, as related by an old native whose memory was a rich storehouse of traditional lore. It is one of the best accounts we have collected of such occurrences in past times, and casts a considerable amount of light of native customs and Maori mentality. It includes several divergences from the main story, but is given as it was told by the old expert. The relater was a native of the Wai-rarapa district, where dwell the descendants of Tara. When the descendants of Tara, Tautoki, Ira and Kahungunu were expelled from the Wellington district early in the nineteenth century, most of the refugees went to Wai-rarapa, where their descendants are still living. The translation has been made in a fairly literal manner, in order to illustrate certain interesting idiomatic usages - to resort to paraphrase would detract from its interest.

Perhaps the most interesting feature of the above narrative is the proof provided by oral tradition that, in the days of Tara, say seven hundred years ago, the present Mirimar peninsula, the Hataitai of the modern Maori, was an Island. This is distinctly shown and is a legend well worthy of record. It is also made fairly clear that, in those days, the western entrance channel extending from Lyall to Evans' Bay was shoal water.

The cultivated food product termed korau mentioned as having been grown on Somes Island, is alluded to in many of these old traditions, and it constitutes a puzzling matter. It is described as a turnip-like root, and our introduced swede turnips are called by the same name. Many natives stoutly maintain that this food plant was grown here for centuries prior to the arrival of Europeans, yet no one of our early voyagers appear to have seen it.

Like all Maori narrators, our expert speaks in a very loose manner in regard to contemporaries of any person under discussion. Thus Whatonga is said to have resided here with his grandchildren, while his own grandfather was still living, which is hardly likely to have been the case, though not impossible. Certain discrepancies are always liable to appear, and do so appear, in such oral traditions.

It may be of some interest to relate how the above tradition came to be recited at a native meeting held fifty years ago, as told by the person who wrote down the story : - On the 7th of March in the year 1867, when we were at Kete-pakaru, Te Waitere and Kereopa said to Moihi Te Matorohanga:- "O Sir! Tell us who settled the coastal lands between Heretaunga (Napier district) and Wai-rarapa.

Moihi replied:— - I am weary of telling you the treasured tales of the men who retained the old-time lore; you so frequently interrupt me when I do speak."

Kereopa remarked : - " Sir ! Your elder, Te Ura-o-te-rangi, is the one who hinders your recitals."

Te Matorohanga replied: - "Very well. It shall be just an ordinary discourse for ourselves. I will commence to trace out these matters from the region of Turanga-nui-a-Rua (Poverty Bay) at the rawhitiroa (east)." Here he began the story as given above.

Maori linguists will note the definite remarks as to the fact of Miramar being an island in the days of Tara in several passages, e.g., " Ko te motu nui rawa kei te pu o te tonga, ki te puau o nga rerenga e rua ki waho ki Tahora nui a Hine-moana," followed by " Engari nga motu ririki e rua." As also:- "Ka haere ki te mataki i nga ngutuawa o te moana, me te motu nui o waenganui o anu awa e rua." Other such passages will be noted in the narrative.

The instructions given by old Whatonga in regard to the construction of the fortified village on the ridge above Worser Bay, the defensive works on eitlier side of the path leading to the water supply, the preparing of a place of refuge in the forest, the storing of food supplies, and the instituting of small outposts, give us a very good idea of Maori life and self-reliance in the stone age. Not less interesting is the lecture on the use of arms, and the novel practice of watching the big toe of the foremost foot of an adversary.

The curious admixture of shrewd sense, highly trained skill, and superstition observed in this narrative is illustrative of the Maori character, and is a common feature in all such recitals.

The tale concerning Te Rangi-kai-kore and the captive woman Hine-rau is a pleasing one, showing that the neolithic Maori occasionally exhibited traits not usually looked for among a cannibal people.

The story of the attack by Mua-upoko avengers on Motu-kairangi is a stirring one, and such episodes have been numerous in the history of old time Wellington. The doleful braying of the war-horns across the waters of Te Awa-a-Taia is no longer heard as of yore, but the raucous shriek of motor cars is no mean substitute therefor. The loose march of the Mua-upoko raiders along the sands of Te One-i-Haukawakawa (Thorndon beach) has been excelled by the orderly tramp of 500 of the descendants of Toi, the wood-eater, as they passed to war in far distant lands beyond the red sun.

The name of the former water channel between Lyall and Evans' Bays is sometimes given as Te Awa-a-Taiau, instead of Te Awa-a-Taia. The name of the present entrance is Te Au-a-Tane, but is occasionally given as Te Au-nui-a-Tane.

The coming of the 'Takitimu' canoe from Eastern Polynesia must have occurred long after the time of Tara, though a reference to it is here inserted.

The first mention of the numbers of Ngai-Tara at the time of the Mua-upoko raid is evidently an error, or the word hundred is understood. The second statement of six hundred is very likely one of the loose statements so frequently made by natives when dealing with numbers. If that number be correct then the raid must have occurred long after the time of Tara.

The cremation of the bodies of the slain chiefs at Houghton Bay illustrates an old custom, that of burning the bodies of persons killed in enemy country. The names of chiefs only of those slain are preserved in tradition, those of commoners are forgotten.

Of the place names round Whetu-kairangi mentioned as being occupied by the raiders, the location of Te Mirimiri and Takapuna has not been ascertained, but these places were probably on the ridge north and south of the pa, which was on the ridge-top above the spring known as Te Puna-a-Tara and Te Puna-a-Tinirau, in Worser Bay. A few other place names have not been located.

The descendants of Tara occupying this district adopted the tribal name of Ngai-Tara, while those of Tautoki took the tribal name of Rangitane, after the son of Tautoki.

The Wai-pahihi stream may be the Karori or Oterongo, while the Wai-kohu can scarcely be any other than the eastern tributary of the Karori stream, the upper reaches of which served as part of the boundary of the land grant to Ngati-Mamoe. It is, however, now impossible to identify some of these old place names, as they were not acquired and preserved by the tribes who took possession of this district a century ago. Te Kopahou is the range on the eastern side of the headwaters of the Kai-wharawhara stream. Te Hapua-o-Rongomai is probably at the mouth of the Owhiro stream. It was so named, because the atua or god Rongomai (personified form of meteors) was seen to descend at that place.

Another version of the story of the naming of the harbour runs as follows - To Umu-roimata remarked to Tara: - "O Sir ! What name shall we give this sea?" Tara replied:-"Let us call it Tawhiti-nui, after the old home-land of our people."

Te Umu said : - " Not so. Let you (yours) be its name." Even so the harbour was named Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara instead of Tawhiti-nui. This woman is said to have named a number of places around the harbour. She said : - "Let the channel that connects the harbour with the ocean on the eastern side of Motu-kairangi (Sky-gazing Island) be named Te Au-a-Taue ; and it was so named.

Motu-Kairangi, or Miramar Island, was looked upon as the 'fostering parent' of the Ngai-Tara folk, and to it all retreated on the approach of enemies. It was a particularly desirable place of residence so long as the tribe remained weak in numbers, and indeed until it became a peninsula. The bases of the talus slopes on the western side of Te Awa-a-Taia provided some cultivatable ground for the people. Maori occupation of the district has ever been principally confined to the Miramar peninsula (and island) and the coast as far as Owhiro. Occupation of the Thorndon area was a minor quantity, but the Hutt claimed more attention.

Of the chain of forts on Te Ranga-a-Hiwi, the range extending from Point Jerningham to Island and Houghton Bays, the most important is said to have been Te Aka-tarewa. It was the residence of Hine-kiri, daughter of Te Rangi-kai-kore, a famous personage of her-generation.

It has been seen that the boundary between the lands of Tara and Tautoki ran up the Hutt river and along the Tararua range. Such a boundary is alluded to as a waewae kapiti, and Kapiti island is said to have been named from this circumstance. Said Tara to his brother: - "Let us name this island after our waewae kapiti." This curious, expression signifies legs (or feet) side by side, or joined.

As other clans moved southward in search of lands, they were directed to available areas, or granted land on which to settle. Thus were the Mamoe folk located on the Pahua lands, and Mua-upoko in the Otaki district.

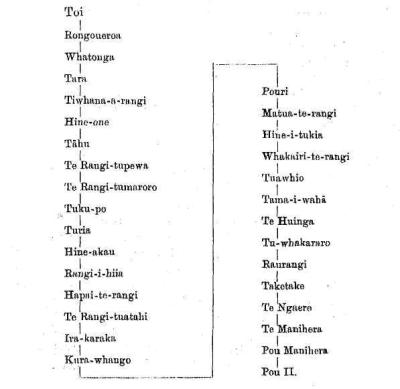

The following genealogy shows the descent of a Wai-rarapa family from Toi, the Polynesian voyager, through Tara. Te Manihera was well-known to the early white settlers of Wellington. The line is taken from Vol. VII, of the "Journal of the Polynesian Society":-

The Ngati-Mamoe or Tini-o-Mamoe people who took refuge here when compelled to leave the Napier district, were an aboriginal folk, a section of the Mouriuri aborigines. A clan of these aboriginal folk, known to the Maori as Maruiwi, occupied the Heipipi pa, situated on a ridge near Petane, a few miles north of Napier, on the coast, the remains of which can still be seen extending for half a mile along the ridges. Yet another band or tribe of aborigines known as Te Koau-pari, occupied lands about Mohaka river in Hawkes Bay. One of the principal chiefs of Te Tini-o-Mamoe, when residing in the Napier district, was one Orotu, after whom the inner harbour at Napier was named Te Whanga-nui-o-Orotu. The prefix Ngati in the tribal name has evidently been added by the Maori, and the eponymic ancestor Mamoe has not been fixed, inasmuch as there were two ancestors of that name, viz., Whatumamoe; sixth in descent from Tamaki, and one Mamoe who flourished seven generations after Whatu.

The pressure of emigrants from the north caused both the Mamoe folk and Muruiwi of Heipipi to leave the Napier district. The latter, curiously enough, moved north to the Bay of Plenty and settled at Te Waimana, where their earthwork forts of Mohoao-nui, Mapouriki and others are still in evidence. This northward movement is a puzzle, because the pressure that caused it came from the north, from the East Coast. It is probable that this movement of Maruiwi occurred long after the departure of the Tini-o-Mamoe.

The increasing population of the north that caused clan after clan to march southward in search of new homes, seems to have been the result of the arrival of many vessels from Eastern Polynesia, and the intermarriage between their crews and aboriginal women. Thus it is a fair presumption that these movements of tribes occurred long after the time of Toi. That of Maruiwi to the Bay of Plenty is shown by genealogies to have taken place about ten to twelve generations ago.

When Ngai-Tara handed over the Pahua lands to Ngati-Mamoe, the latter constructed two fortified villages on the coast. Though possessing, as the Maori puts it, two baskets of food, represented by the ocean and the forest, the former one was the more important of the two. One of these pa, or fortified villages, known as Makure-rua is said to have been situated at or near Te Rimurapa, and just west of the Waipapa creek, which has a rocky bed. The pa contained two tiki (summits, hills or hillocks), and the spur end at Sinclair Head seems to be the only place in that vicinity that fits the description. Moreover there are signs of occupation on the top of the bluff, showing that the place has been occupied at some time. If this is Makuro-rua, then the creek between Sinclair Head and the Red Rocks is Wai-papa, though most of these creeks have received more modern names, given by the Awa tribe.

Their other pa was Wai-komaru, and it is said to have been located on a ridge west of Sinclair Head. Its site was probably on the narrow ridge, about a mile west of the Head, that diverts the course of the Mangarara stream, and prevents its running straight out to the bench.

This occupation by Ngati-Mamoe is said to have been directed by their chief Tu-kapua, a great grandson of Orotu, or Rotu, though genealogies of the aborigines are a somewhat doubtful quantity.

| There is apparently no record of any fighting betvveen Ngai-Tara and the Mamoe clan, and tradition states that, though the latter were at first suspicious of their neighbours, this feeling wore off and the two tribes became friendly. The length of the sojourn of the migrants in this district is not clear, but one version of the story is that they moved on to the South Island prior to the death of Tu-kapua. Another story is that they left here eighteen generations ago, say about the year 1460. |

Mr. J. A. Wilson has recorded a tradition that an old time tribe, known as Te Tauira, formerly lived at Te Wairoa, Hawkes Bay, that they were expelled from that district by Rakui-pāka and fled southward to Wai-rarapa. A tradition states that Otauira, a strewn near Featherston, was named after them. Tauira, the eponymic ancestor of that clan is said to have married Te Ipuahau of Bay of Plenty, and begat Kopura, an ancestor of Taiaroa of Ngai-Tahu. Mamoe (the ancestor of that name) was connected with Te Tini-o-Rua-tamore, an aboriginal clan of the Napier district that sought shelter from northern invaders in the Seventy Mile Bush. Thus we see that bands of the original inhabitants were driven southward by pressure from the mixed race of the north, and that some at least of them passed through this district on their way to the South Island. The above tradition gives Paetu-mokai as the name of the site of Featherston.

The eponymic ancestor of the Tauira clan is said to have met Toi at Tonga-porutu - some forty-five miles north of New Plymouth.

The old men have told us that one of the pa or fortified villages of Tara, known as Rangi-tatau, was situated on the western side of the entrance to Port Nicholson, opposite Pencarrow Head. It was probably either on the hill at Palmer Head, or on the hill immediately west of the little stream at Tarakena, the old Pilot station between Lyall Bay and Seatoun. On both of these hills are to be seen signs of old time occupation. Those on the last mentioned hill are the most distinct, and included excavated hut sites in the form of small terraces, a small broken scarped face, originally part of the defences, and the butt of a totara post still in position.

The principal house in the Rangi-tatau pa was named Raukawa. A small stream hard by was known as Te Poti. A famous fishing rock off shore, where hapuku were caught, was called Te Kai-whata-whata.

The Rangitane tribe, as it increased in numbers, gradually occupied the whole of the Wai-rarapa district, and then spread northward to the Napier district. This occupation, however, was that of neolithic man, not that of civilised man. They dwelt in small and scattered communities over this region, principally on the open lands and within reach of the sea. The forest held but few inhabitants; they possessed no tools whereby to destroy it, nor did they desire to reduce the area, for was it not one of their principal food baskets ? In later times many crossed the Straits and settled in the Sounds, where they are represented by the Ngati-Kuia folk of Pelorus. Others settled in the Rangitikei district, while those who remained on the old tribal lands, assumed in later generations the tribal name of Ngati-Kahungunu. An old tribal aphorism of this people - " Rangitane tangata rau," betokens their reputed numbers in past times. Another of there pithy sayings applied to them is - " Rangitane nui a rangi."

Tara is said to have lived inland of Napier at one time, where Te Roto-a-Tara, a lake, was named after him. Both this and Poukawa lake are said to have been eel preserves of his, while Te Roto-a-Kiwa is called his bathing place. Connected with the Te Roto-a-Tara is the myth of Te Awarua o Porirua, a huge taniwha or water monster that originally dwelt in Porirua Harbour, but shifted its quarters to the above lake, where it formed the islet in the lake. [The full story of Te Awarua-o-Porirua is to be found in "The Maori Wars of the Nineteenth Century, " 2nd edition, p. 288.] Hone Wairere of Whanganui informed the writer that Porirua was so named, from the fact that it possesses two arms or channels (ko Porirua, mo te ruanga o nga moana te take, koia a Porirua). As, however, several other origins are given for this name, it is clear that the Maori knows little about the matter.

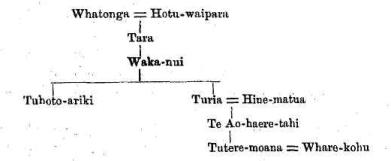

It would appear that Whatonga returned to this district, for we are told in tradition that his remains were placed in the famed burial cave named Whare-kohu, situated at the southern end of Kapiti island. His wife Hotu-waipara, his son Tara, Tuhoto-ariki (grandson of Tara), Turia (brother of Tuhoto), Tutere-moana (grandson of Turia) and many another of the chiefs of Nga-Tara found their last home in that old tribal burial cave, though presumably their bones only were conveyed thither, after exhumation in the manner Maori. The cave was named after a woman, the wife of Tutere-moana, and the latter so named it. Te Ao-haere-tahi was buried at Kahu-ranaki, at Heretaunga (Napier district).

The death of Wakanui, son of Tara. (pp.37-38)

| Lament for Wakanui | |

| "He aha ra taku taha huahuaki nei | |

| Ka hewa noa o te ngakau he marie aronui | |

| Ka maaha noa o roto i au | |

| Kaore ia ko koe tonu e kai arohi nei i au | |

| E rangi aku, a whakaruhi nei i au | |

| Aua ki au ! | |

| E rangi aku, he aha rawa ra to kino ki au | |

| Aue ! Ko Whiro te tipua manatu ra pea | |

| Ko te take o te kino i takoto ai | |

| Ki roto o Tu-te-aniwaniwa | |

| Te whare ra tena i whakatipuria mai ai | |

| Maiki-nui, Maiki-roa, Maiki-ahua | |

| Maiki-whekaro, Maiki-pupu rau wha | |

| Maiki i taupuru, Maiki ka wheau atu na koe | |

| Ki Tuahiwi nui o Hine-moana | |

| Ko to ara tena i whano mai ai koe | |

| Ka hoki atu na koe ki te wa kainga | |

| Ki o tipuna i Tawhiti-nui | |

| I roto o Pari-nui, o Pari-roa, o Pari-ikeike | |

| Nga whare ra tena i noho ai | |

| Ka ta ra e te manawa taki, te manawa kaipara | |

| Ka toha rikiriki ki te nuku o te moana | |

| Koia to tipuna, a Toi-te-huatahi | |

| I kohau ai i 'Tiritiri o te moana' nei | |

| Nana taua i makere mai ai i Hawaiki | |

| I runga i a Kura-hau-po | |

| Ka tau ana Tonga-porutu | |

| Ka tau ana taua Whakatane | |

| Ka tangi te mapu toiora i a taua | |

| E tama ... e ..i | |

| E rangi aku, inaia koe ka tatara rawa ki tawhiti | |

| Tahuri mai ki au ; tenei to manawa | |

| Ko te manawa o Ka-hutia-te-rangi | |

| Hei waka atu mohou | |

| Kia u atu koe ki Irihia, ki Hono-i-wairua | |

| E Wakanui ...e..i" |

(Wherefore doth this omen afflict me? The deluded heart thought fair fortune approaches, hence joy filled my soul. Not so, 'tis yon who causes me worry and grief. O lad ! Thou hast unnerved me. Alas ! Ah me ! O my lad! Why did you forsake me ? Alas ! "Tis the act of dread Whiro, who abideth within Tu-te-aniwaniwa, the place where-from come all ills that afflict mankind, and by whose influence were you lost in surging billows of Hine-moana. That way it was by which ye hither came, and by which ye shall return to the homeland, and to thy ancestors at Tawhiti-nui, who dwelt within Pari-nui, Pari-roa and Pari-ikeike, and knew untroubled calm ere far scattered o'er the ocean we became. Hence came thy ancestor Toi-te-huatahi, searching vaguely across vast ocean spaces, and causing us to leave for Hawaiki on ' Kura-hau-po,' to sojourn at Tonga-porutu and Whakatane, where ended the long quest, and joy and peace were felt. O son ! O my lad ! Thou who art now afar off; turn to me. Here is the spirit of thy ancestor, of Ka-hutia-te-rangi, to serve as a vessel to bear you onward, to land at Irihia, at Te Hono-i-wairua. O Wakanui! ")

Notes: -

Whiro. - The origin or personified form of disease and death.

Maiki-nui, etc. - Personified forms of disease and such afflictions.

Tuahiwi nui o Hine-moana. - Central ridge of the ocean, marked by rough seas.

Hine-moana. - Personified form of the ocean.

Tawhiti-nui. - A place at which the ancestors of the Maori sojourned during their voyage from the fatherland.

Irihia. - The fatherland of the Maori race.

Te Hono-i-wairua. - A place in the original homeland where the spirits of the dead meet ere going to the spirit world.

The above lament is a fine composition in the original, bearing the impress of age, and containing allusions to quaint old myths and beliefs of the Maori folk.

Part II continued - The coming of the Kahungunu folk. (p. 39-)

Korero o te Wa I Raraunga I Rauemi I Te Whanganui a Tara I Whakapapa