The Spectacular Cinemas of Wellington

For much of the 20th century, entertainment was dominated by movie theatres. Many of our early cinemas grew from live theatres following the first screening of motion pictures in the capital in 1896.

The Plaza Cinema, Manners Street, ATL Ref: 1/2-100179-G

For the next decade, short films of around two to four minutes in length often became a part of local vaudeville shows where they would appear on a programme of entertainment along with live song and dance routines, magicians, jugglers and trained animal acts. Interest in the new medium increased with the onset of the Boer War, with people clamouring to see footage of “our boys” in South Africa which followed the filming of troop departures from Wellington in 1900 (the oldest surviving film footage to be shot in New Zealand). Films also began to be shown in the Wellington Town Hall, as well as various community and church halls, but a new era began in 1910 when the Kings Theatre opened in Dixon Street as New Zealand’s first purpose-built cinema. Four years later it became the venue for the Wellington screenings of Hinemoa, New Zealand’s first (silent) feature film, with a musical accompaniment provided by the cinema’s own in-house orchestra. Though movies remained popular during the First World War, the conflict saw a resurgence in more community-focussed entertainment such as rallies, dances and mass-singing events. Restrictions on the supply of building materials during the war saw a halt to most cinema construction (the only significant theatre to open during this time was the Paramount in Courtenay Place in 1917), but the inter-war period which followed was to become the ‘Golden Age’ of movie theatres.

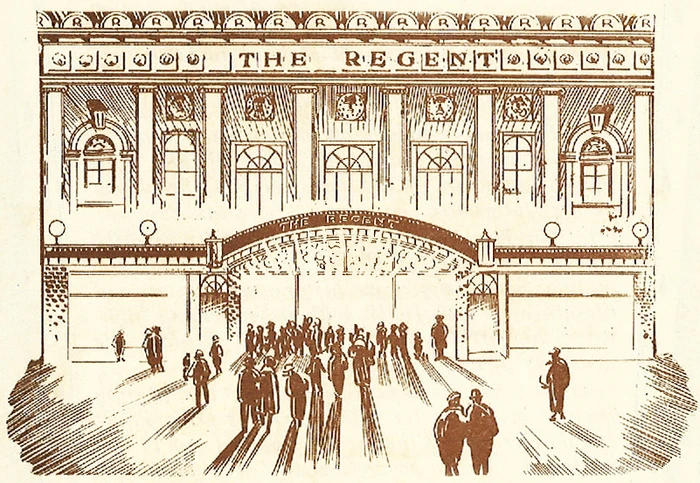

The Regent in Manners Street typified the glamour of the ‘Spectaculars’ when it opened in 1926. It was demolished in 1979 and was replaced with Wellington’s first purpose-built ‘multiplex’ cinema which operated under the same name until its closure in 2009.

In 1924 the De Luxe opened in Kent Terrace (later to be renamed the Embassy in 1945) which was soon followed by the Regent on Manners Street in 1926, the Majestic on Willis Street in 1928 (which also included a cabaret), the State on Courtnay Place in 1933 and the Plaza abutting the James Smiths Department Store in 1934. These grand ‘palace theatres’ (aka ‘the Spectaculars’) were lavishly furnished with luxurious interiors designed to ‘wow’ audiences and make every visit feel like a special occasion. Wearing one’s best outfit and visiting the hair salon before going to the movies became de rigueur. The capacity of these cinemas was enormous, the largest being the Majestic which had 2221 seats while the Embassy had 1725 seats when it opened as the De Luxe (since reduced to 820). This period also saw the rise of simpler suburban movie theatres such as the Regal in Karori, the Empire in Island Bay, the Ascot in Newtown and the spread of cinemas across the Hutt Valley and beyond. New technology saw rapid changes occur, as the orchestras which had provided live music and sound effects for silent films gave way to Wurlitzer organs. Though these were a major investment (the De Luxe spent £10,000 installing their organ in 1927, the equivalent of c. $1.2 million today) they were substantially cheaper to operate than employing an orchestra of live musicians for each screening.

Al Jolson’s ‘The Jazz Singer’ revolutionised cinema-going in Wellington when it was released in 1929, nearly two years after its first screening in the United States.

Wurlitzers in turn gave way to ‘the talkies’ when, in August 1929, The Jazz Singer hit Wellington’s screens as the first film to feature a synchronised soundtrack. By the following year, almost every cinema that could began the process of installing sound equipment so they could screen these new films. Some smaller suburban cinemas which could not afford the expense of converting to sound began to close. The transition to this new era of film was sudden and dramatic, by 1930 the production of silent movies had almost completely ceased. Despite the tightening of household budgets during the Great Depression, going to the cinema remained a popular way for people to briefly forget about their troubles as both the Hollywood and British film studios began pumping out ‘talkies’ on a near weekly basis. Seeing a film also became one of the few ways in which courting couples could get a couple of hours of privacy, and a darkened auditorium often became the place to hold hands and perhaps snatch a furtive kiss. Attendances during this period reached extraordinary numbers, hitting record heights during World War II when our population of only 1.6 million people attended the movies nearly 39 million times over 12 months; New Zealand had nearly three times more cinemas per head than did the United States. Many Wellingtonians in the 20 – 40 age bracket would see a couple of films per week, and bookings for Saturday night screenings often had to be made the previous Monday to ensure a seat.

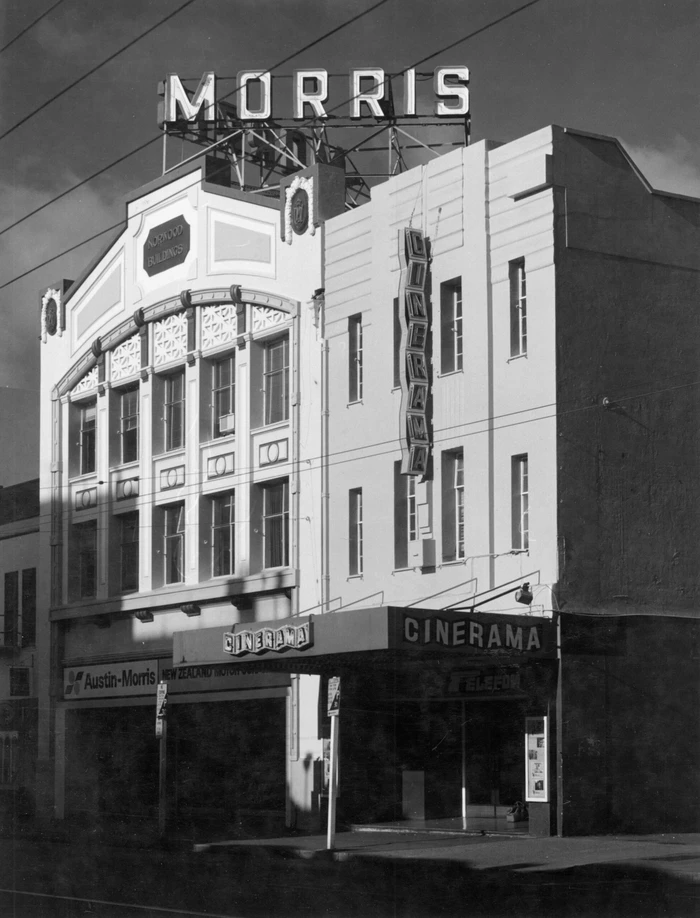

Featuring the largest screen in Wellington, the Cinerama on Courtenay Place became the place to see blockbusters such as Star Wars and Top Gun.

The immediate post-war period saw a gradual decline in movie attendance and no significant new cinemas opened in the city for nearly 40 years, but new formats such as Cinemascope and Vista Vision were introduced to try and win back audiences. The most dramatic of these was a triple-projector, curved screen system called Cinerama which led to The State in Courtenay Place changing its name to match that of the new format. Though this screen was later replaced with a conventional wide-format flat screen (the largest ever installed in a Wellington movie theatre), the cinema retained this name until its closure and demolition in 1987. A combination of these new formats, the first of ‘baby boomers’ becoming teenagers, and blockbuster films such as Ben Hur and Some Like it Hot saw ticket sales hitting an all-time high in 1960 when New Zealanders bought 40 million tickets and went to the movies an average of 17 times each. But a dramatic change for the local cinema industry was about to hit: the introduction of television.

New Zealand was slow to introduce the new technology, with transmissions beginning in Wellington in July 1961 (Australia had regular TV broadcasts from 1956). The expense of purchasing a set, a short daily broadcast of only five hours of a single channel each evening, and the difficulty in transmitting a signal around Wellington’s hills meant the impact of TV on cinema audience numbers was initially quite limited. However, in February 1967 broadcasts shifted from Mt Victoria to a much more powerful transmitter on the summit of Mt Kaukau / Tarikākā + six repeater stations spread across greater-Wellington to fill in signal shadows caused by hills.

The opening of the Mt Kaukau television transmitter had a dramatic effect on cinema ticket sales. The Evening Post, 21st February 1967 (click to enlarge).

Televisions were expensive (a black and white set could easily cost the equivalent of c. $7000 today) but with finance and easy terms being offered by retailers, they soon became the appliance that every household wanted to own. The impact of the opening of the Mt Kaukau TV transmitter on cinema ticket sales was dramatic and most of Wellington’s suburban cinemas were forced into closure by the end of the 1960s as audience numbers plunged. Smaller central city cinemas also began to shut in the 1970s as the process accelerated following the introduction of colour TV transmission in late 1973. The 1980s saw most of the old ‘spectaculars’ close, with owners unwilling to invest in expensive maintenance, refurbishment or new technology. Property developers began to eye up the prime sites they occupied; they were replaced by ‘multiplexes’ featuring multiple screens, comfortable seats, bars, restaurants and Dolby stereo sound. These too gradually began to close as a result of changing tastes or seismic issues. Today the Embassy is the sole remaining example of a ‘spectacular’ in Wellington, but it has since been joined by many other smaller screens following with the unexpected resurgence of suburban cinemas across the region.

In the late 1990s, retired accountant Tony Froude began to research the history of every Wellington cinema and movie hall he could trace. Inspired by his memories of going to the movies as a child in the 1940s, he began to trawl through files held by the Wellington City Archives, microfilmed newspapers at the Central Library, records held by the NZ Film Archive (now Ngā Taonga) and the National Library to build up a comprehensive history of Wellington’s cinema scene. His research was self-published in 2000 in his book Where to go on Saturday night? The interest it generated led to two further books as he expanded his scope to include the Hutt Valley (Big Screens in the Valley) and the western side of the Wellington region covering Tawa to Tokomaru (Reel Entertainment). His interest in cinema design led him to uncover the work of the architect James Bennie (1873 – 1945) who specialised in cinemas but whose other buildings also had a notable impact on Wellington’s streetscape. With permission, these works have now been digitised on our heritage platform and collectively provide the most comprehensive history of movie theatres in Wellington ever published.

Where to go on Saturday night? Wellington Cinemas and Movie Halls, 1896-2000

Big Screens in the Valley : Cinemas and Movie Halls in the Hutt Valley, 1906-2002

Reel Entertainment : Cinemas and Movie Halls in the Twentieth Century, Tawa to Tokomaru