Design and Living by E. A. Plischke

Now digitised on Wellington City Recollect, ‘Design and Living’ published in 1947 offers pertinent solutions to our current housing issues nearly 75 years later.

Ernst Anton Plischke (1903 – 1992) was one of the most notable architects ever to work in New Zealand. Though he produced only a limited number of buildings while living here, his influence on the path that NZ architecture and design would follow in the subsequent decades was considerable. He arrived in Wellington in 1939 from his native Vienna just four months before the start of World War II, having fled here with his Jewish wife and stepson following Nazi Germany’s ‘Anschluss’ with Austria. Settling in Brooklyn, it was in the capital that his influence had its greatest impact. He had impeccable credentials having studied & worked under the legendary German Modernist Peter Behrens, knew Le Corbusier, met Frank Lloyd Wright and had personally designed domestic and commercial buildings in the 1920s and 1930s in Austria that still look contemporary today.

New Zealand’s architecture in the 1930s reflected the conservative Anglo-Saxon culture which was dominant at the time. Plischke was viewed with suspicion due to both his ‘foreign’ ideas on building design and because he was often viewed as being ‘German’. While he didn’t suffer the incarceration that some Germans faced during the war, not being Jewish meant he wasn’t eligible for refugee status so was classed as an ‘alien’ and kept under surveillance during the war years. His first job was as a poorly paid draughtsman with the New Zealand Housing Department, but he soon moved on to creating innovative new state house designs and likely had a considerable role in the design of the Dixon Street Flats. Sadly many of his ideas from this period were altered by senior Government architects before they reached the construction stage. In frustration he shifted to the planning unit of the same department and worked extensively on the layout of the Lower Hutt suburb of Naenae and the design of its amenities but his work was again interfered with by more senior staff. He was also snubbed by the New Zealand Institute of Architects who refused to accept his credentials and admit him as a registered architect. They insisted that he sit a series of NZIA examinations to gain registration. Plischke in turn refused to sit, believing this requirement to be completely demeaning to his proven abilities as an architect. The result was that for the entire 24 years that he lived and worked in New Zealand, he was never able to officially call himself an architect.

Plischke designed this building in 1930 in Vienna for the Austrian Ministry of Employment. Following the 1938 annexation of Austria by Germany, it was vandalised by Nazis who believed that its modern design was ‘Bolshevist’.

However his influence during his early period in NZ was considerable; not just for his designs but also through the lectures he gave at Victoria University. The night-school classes held at the university by the Council of Adult Education were often packed to capacity as word began to spread about this new Austrian immigrant and his wild ‘modern’ ideas. Sadly, senior academics did not have the same belief in Plischke as his students did and his application to head the School of Architecture & Planning at Auckland University was rejected. Plischke was later told that the reason he did not get the position was that he “did not understand the traditions of the English village.” Shortly before leaving the Public Service, he wrote Design and Living while still an employee of the Housing Department and it was published by Internal Affairs in 1947. Again reflecting the era in which it was written, the editors of the book deliberately misspelt his surname, printing it phonetically on the cover and title page rather than using its correct German form.

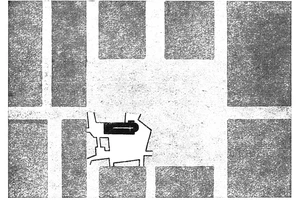

Plischke was critical of the excessive size of ‘squares’ which are a common feature in the centre of many NZ towns and cities. Shown here at the same scale is a typical NZ square (most likely Palmerston North) on which he has overlaid a map of the historic central square and cathedral of Modena in Northern Italy.

The book was written to provide a potential solution to a serious developing problem. Immediately after World War II ended, demobbed soldiers, families and rural Māori flooded into the cities looking for work and new opportunities. New manufacturing plants were being established and in Wellington there was a big jump in the size of the civil service leading to a new generation of ‘cadets’ starting their careers as public servants. Coupled with this was the start of the Baby Boom and severe shortages of building materials as so much of the economy had been directed towards the war effort. Plischke identified the looming housing crisis and published this work, fusing together his thoughts on design, planning and architecture, essentially as a manifesto to encourage both planners and the public to think differently about how New Zealand towns and cities might develop. Though the ‘International Style’ of modernism associated with Plischke has often been criticised for imposing an extreme rationality on building design to the exclusion of vernacular architecture, his philosophy went beyond the modernist vs vernacular debate.

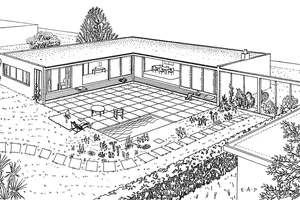

Plischke’s suggested design for an inexpensive small modern home arranged to make maximum use of space & sun and orientated around private courtyard rather than facing the street; radical concepts in the 1940s.

He recognised that modernism was often perceived to be elitist and expensive even though this was the antithesis of its original principles. As such, he regularly included projected costings of his proposed designs and how they came in below the government grants for affordable housing. Most striking is his prophetic belief that New Zealand’s method of construction, house design and planning was unsustainable and would eventually lead to urban sprawl and increasing costs. His solutions were an anathema to many at the time but today seem eminently sensible; build smaller houses, design their interiors and fittings to make their smaller size just as liveable as a larger home and adjust the expectations of the public in terms of what they should expect from a house. Kiwi-quarter acre housing developments could not go on for ever and well designed multi-units in planned, community-focussed suburbs were a potential solution; ideas that would take decades before they became common currency among planners and the public. He also felt that well-planned smaller, compact cities with higher densities of population would lead to advances in the arts, business and culture; much as they had done in his native Vienna where what we now call ‘café culture’ first appeared in the late 17th century.

Shortly after the book was published, Plischke finally left the Housing Department after working for them for eight years. With no sign that his status would be formally recognised by the NZIA, he formed a partnership with the locally qualified architect Cedric Firth that enabled him to begin a private practice. Their largest and most significant commission, Massey House on Lambton Quay, was from the NZ Dairy and Meat Boards and it revolutionised office design in New Zealand. Likely inspired by Lúcio Costa & Le Corbusier’s Ministry of Education building in Rio de Janeiro, it was New Zealand’s first modern glass curtain-walled office building and became hugely influential. This photomontage released shortly before construction began shows the proposed structure juxtaposed alongside the existing Victorian and Edwardian streetscape of Lambton Quay (complete with tram tracks). One can only imagine the impact the building must have had on Wellingtonians in the mid-1950s.

Plischke went on to design a number of ground-breaking modernist houses for private clients as well as several larger buildings such as a Catholic church in Taihape and a community centre in Khandallah. Many of his commissions were to come from those with a similar background as himself; the highly-educated intelligentsia many of whom had also left Europe just before or after the War. He often insisted on taking complete control of both the interior and exterior designs of his buildings though his wife Anna often assisted him in choosing the wood veneers, fittings and fabrics, as well as landscaping the gardens.

News of his work began to filter back to his home city of Vienna who distinguished him with the Preis der Stadt Wien in 1963 (“Prize of the City of Vienna”). Shortly after this he was offered the position as head of one of the world’s most prestigious architectural institutions, the Master Architecture School at the Academy of Fine Arts of Austria. He was at first reluctant to accept this as he was 60 at the time, but in 1963 he decided to leave Wellington and return to his home country. As well as teaching and administering the school, he took a number of private commissions and received several honours and awards. One of those was finally to receive recognition from the NZIA when he was bestowed with an Honorary Fellowship of the New Zealand Institute of Architects for which he re-visited Wellington for his investiture in 1969. He continued to teach small classes well into the 1970s before going into a reluctant retirement. He kept in close contact with the academy and the architectural fraternity until his death in Vienna in 1992 at the age of 89.

Design and Living is now available to read and is fully searchable on Wellington City Recollect.