The Land of Tara and they who settled it, by Elsdon Best

Part IV. pp. 76-

An incident related to the writer by Honiana Te Puni of Pito-one is, I believe, attributed in error by him to the above raid by Nga-Puhi related on a previous page. It may have pertained to one of the later raids from the north. It appears that an invading force captured some prisoners and canoes at Porirua. Some of the party came on by canoe, and the rest marched along the coast. After passing Tarawhiti the wind rose, and on reaching Sinclair Head the sea at that point was very rough. Here one of the vessels was capsized and her crew perished in the wild waters among the rugged rooks of the headland. When the men on board saw that the canoe must be swamped or capsized, some seized their muskets and fired a volley as a farewell to their friends on the beach, who could only stand helplessly and watch the death of their kinsmen. But they did at least fire another volley as a tohu mamae and farewell greeting. So the raiders went down into the depths of Hine-moana, as many thousands of their race have done in the days that lie behind.

The Amio-Whenua Raid, p 76

Cook's Vessel anchors at Wellington heads pp. 77-79

We must presume that Captain Cook was the first European seen by the Ngati-Ira folk. Some of these natives visited Queen Charlotte Sound during Cook's stay there when on his first voyage. Possibly they had seen his vessel in the Straits, and curiosity led them to the Sound.

On his second voyage, after leaving the above Sound, Cook attempted to enter Wellington Harbour, but failed to get in, as seen in the following account written by him : - "November 2, 1773. "We discovered on the east side of Cape Teerawhitte a new inlet I had never observed before. Being tired with beating against the N.W. winds, I resolved to put into this place, if I found it practicable, or to anchor in the bay which lies before it ...... At one o'clock we reached the entrance of the inlet, just as the tide of ebb was making out; the wind likewise against us, we anchored in twelve fathoms water, the bottom a fine sand. The easternmost of the Black Rocks, which lie on the larboard side of the entrance of the inlet, bore N. by E. one mile distant; Cape Teerawhitte, or the west point of the bay, west, distant about two leagues; and the east point of the bay N. by E. four or five miles.

Soon after we had anchored, several of the natives came off in their canoes; two from one shore, and one from the other. It required but little address to get three or four of them on board. These people were extravagantly fond of nails above every other thing. To one man I gave two cocks and two hens, which he received with so much indifference as gave me little hopes he would take proper care of them.

We had not been at anchor here above two hours, before the wind veered to N.E., with which we weighed, but the anchor was hardly at the bows before it shifted to south. With this we could but just lead out of the bay."

A perusal of the above seems to show that Cook applied the name of Cape Teerawhitte, as he calls it, to Sinclair Head, which is about six miles from his place of anchorage off Palmer Head. A New Zealand Company's map of the Wellington district, dated January 4, 1843, has Tongue Point marked as Cape Terrawittee, but that point could not be seen from Cook's anchorage, and moreover is too distant. In later times the name was transferred (as Terawhiti) to the point on Section 11, at the southern end of the Omere range, the correct native name of which place is Tarawhiti.

To an ignorant landsman it seems strange that Cook did not enter the harbour when the wind shifted to the south. Had he done, so he would have left us some interesting observations on the Land of Tara in neolithic times. That ebb tide has much to answer for.

Cook makes no mention of any village seen, though apparently natives were living on both sides of the entrance. Had the old stockaded villages that once stood on the hill tops at Tarakena, Palmer Head, and Point Dorset then been occupied, one would expect some mention of the fact, for they would be clearly seen from the vessel, or at least the first mentioned two would. The natives may, at that time, have been living in the small hamlets such as that in the mouth of the gully at Tarakena, and such places would be by no means conspicuous.

[Maori pa, Palliser Bay and cape, painted by Samuel Brees, 1844?], Alexander Turnbull Library Reference no B-031-018.

Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington must be obtained before any re-use of this image.

Forster gives us more particulars about the appearance of the harbour and its surroundings as seen 144 years ago than does Cook. His remarks are apt, save that concerning the gentle slopes, which do not seem to have been rediscovered yet. His statement as to a scant population supports a conclusion arrived at by the writer many years ago, viz., that this district could never have supported even a fairly large population. His concluding remarks read like those of a prophet, when one remembers the circumstances that saved the early European settlers of Wellington from disaster, and the natural sequence of the extraordinary conduct of affairs by the New Zealand Company.

Captain Furneaux, of the 'Adventure' (Cook's second voyage), did not approach Wellington Harbour, but communicated with the natives near Cape Palliser on November 4, 1773. He says: - "On the 4th of November we again got inshore, near Cape Palliser, and were visited by a number of natives in their canoes, bringing a great quantity of crayfish, which we bought of them for nails (spikes) and Otaheite (Tahiti) cloth (tapa or bark cloth)."

If permissible it be to look into the future, we will see what D'Urville said about the harbour, ere returning to our cosas de Maori. This French voyager came through the French Pass on January 28, 1827. On the 29th he was driven down towards Cape Campbell, whence he steered for the North Island, intending to explore the coast west of Cape Palliser. He wrote: - "To my great regret the wind did not permit us to gain a deep bay between Cape Poliwero and Cape Tourakira (Turaki-rae), where are found some isles near the shore which should offer excellent anchorages."

D'Urville's Cape Poliwero is Pari-whero (Red Cliff) at Sinclair Head, which name the Wai-rarapa natives gave him. He anchored on the west side of Palliser Bay, where canoes went off to his vessel, and two of the natives sailed with him as far as the Tologa district. An account of his coastal trip, translated, by Mr. S. Percy Smith, was published in the "Transactions of the New Zealand Institute," Vol. XLI., p. 130.

On McDonnell's map, of later days, Cape Poliwero was shifted to the place we now know as Cape Terawhiti

Ngati-Awa, of Taranaki, occupy the Land of Tara. Ngati-Ira driven from the district. pp. 79-82

We will now see how the sons of Ira, the Heart Eater, were expelled from the Harbour of Tara by invading people from the Taranaki district, who were compelled to desert their old-time homes by the raids directed against them from the Waikato district. A mere outline of these movements will here be given, inasmuch as the particulars thereof have already been published in Vols. I. and X. of the "Journal of the Polynesian Society," and "The History and Traditions of the Maori of the West Coast," by Mr. S. Percy Smith.

In the year 1822 the Ngati-Toa tribe of the Kawhia district, hard pressed by Waikato gun-fighters, left their ancestral homes and marched southward in search of new homes. These people were under the leadership of Te Rau-paraha, who, in his previous trip south, had observed the fat lands of the Otaki district, and his desire was toward them. After some severe fighting the migrants reached the vicinity of Normanby, where they camped at a place known since as Te Puni-o-Paraha. The Ruanui tribe was hostile, and for some time prevented any further advance, but the migrants eventually reached the Otaki district, and occupied Kapiti Island in 1823. They at once set about tranquillising the country in the truly German manner by murdering the inhabitants, pretty soon but few of the Mua-upoko tribe were left.

In 1824 many of the Ngati-Awa tribe came down from Taranaki to the Otaki district, and in the years 1825-26 they moved on and invaded the Wellington district, from which area they soon expelled Ngati-Ira. Some settled at Owhariu, Wai-ariki, and other places on the coast, others came over to the Harbour of Tara and settled at Te Aro, Kumu-toto, Nga Pakoko, Pipi-tea, Te Rae-kaihau, Kopae-parawai, Tiaki-wai, Raurimu and Pa-kuao, all of which places may be seen on the map between Te Aro flat and the eastern end of Tinakore Road. Other settlements were at Kai-wharawhara, Nga Urangu, Pito-one, and at Hikoikoi and Ohiti on either side of the Hutt river.

When these new settlers arrived here, the Ngati-Ira folk were living on the eastern shore of the harbour, where some of Forster's gentle slopes are. They had villages at Wai-whetu, Te Mahau, Whiorau, Okiwi, Paraoa-nui and Kohanga-te-ra, from all of which places they were driven by Ngati-Awa in a series of fights in which the latter seem to have been the aggressors. At about the same time Ngati-Toa were ejecting Ngati-Ira from the Porirua lands by the same methods.

At Ngutu-ihe, below the road that ascends the range and leads to Wainui-o-mata, Ngati-Ira had a stockaded village, while another such was Korohiwa, on the beach opposite Mana Island, of which place Te Ao-paoa was chief. Apparently Ngati-Ira had a firm faith at one time in their power to hold these lands, as witness a tribal aphorism :- " Kia mahaki ra ano te Kauwae o Poua, katahi ka riro te whenua." When the Kauwae o Poua becomes loose, then only will the land pass into other hands ; the Kauwae o Poua, or Jawbone of Poua, being a wave-washed rock at Te Rimurapa.

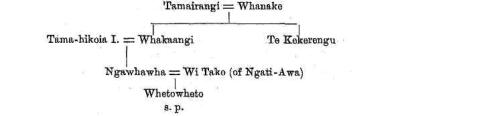

Thus Ngati-Awa, under the chiefs Patu-kawenga, Ngatata, Te Arau, Te Poki, Pomare, Whare-poaka, and others harried the hapless sons of Ira, who were compelled to fall back to Wai-rarapa. Some are said to have sought refuge on the Tapu-te-ranga islet at Island Bay, from which place, on being attacked there, they retired to Owhariu, where some were captured by Ngati-Awa. Among these prisoners were Tamairangi and Te Kekerengu, wife and son of Whanake, the principal chief of Ngati-Ira, who later escaped to the South Island, where they were slain by the Ngai-Tahu folk, hence the place name of Kekerengu in those parts. This man, Te Kekerengu, was the owner of the famous greenstone mere called 'Tawhito-whenua,' to whom it had been given by Kotuku. He gave it to Te Rangi-haeata, of Ngati-Toa, who gave it to Hohepa Tama-i-hengia, of Porirua. Subsequently it came into the possession of Airini Karauria (Mrs. Donnelly).

This table shows a junction of conqueror and conquered, the late chief Wi Tako having married a grand-daughter of the chieftainess Tamairangi. The latter was one of three famous women of East Coast tribes whom history tells us were carried in litters when they moved abroad, on account of the respect in which they were held.

The song of lamentation sung by Tamairangi when driven from her home we have not been able to collect, but the following lament for Te Kekerengu is worthy of preservation: -

" He aha rawa te hau e tokihi mai nei

Ki taku kiri . . e . . i

He hau taua pea no te whenua , . e . . i

Waiho me kake ake pea e au

Ki runga o Te Whetu-kairangi

Taumata materetanga ki roto o Te Whanga-nui-a-Tara

Auo ki au! E koro ma . . e . . i

Ko Matiu, ko Makaro anake e kauhora noa mai ra

Nga whakaruru hau taua i etahi rangi ra . . e . . i

Naia koutou ka ngaro i au . . e . . i

Kai aku mata ki nga ope

Ka takoto ki Waitaha raia

Ka ngaro whakaaitu ia koutou

E koro ma ! E kui ma . . e !

Tera pea koutou kei o takanga

I roto o Porirua ra

Ko wai au ka kite atu i a koutou

E koro ma . . e . . i.

Aue . . i !

Me kai arohi noa e aku mata

Ki o titahatanga i Arapaoa ra . . e , . i

Te ata kitea atu koutou

E koro ma ! E kui ma . . e . . i!

I te rehu moana e takoto mai ra . . e . . i

Tena rawa pea koe kei tapua (?) tahi o Tuhirangi

E taki ra i te ihu waka

Koi he koe i te ara ki Te Aumiti

Kei whea rawa koutou e ngaro nei i au

E koro ma . . e . . i

Tena rawa pea koutou ki roto o Tai-tawaro

E ngaro nei . . e . . i

Ko te waro hunanga tena o Tuhirangi

Nana i taki mai te waka o Kupe,

O Ngake, ki Aotearoa

Ka mate Wheke a Muturangi i taupa o Raukawa

Koia Whatu-kaiponu, whatu tipare

Ka (hoe) atu ki Te Aumiti

E whakaumu noa mai ra

Tauranga matai o te Koau a Toru paihau tahi

E kai mai ra ki te hau

Ka ngaro raia koutou i au, e koro ma . . e . . i

Tena pea kei roto o Whare-rau i Waipuna

Kei roto o tiritiri te moana i roto Pukerua

Ka wehe nei koutou i au ...e... i."

(What wind is this that smites my skin; the wind of war may be from other lands. Let me perchance ascend to the summit of Te Whetu-kairangi and scan the expanse of the Whanga-nui-a-Tara. Alas! Ah me! O Sirs! Nought is seen save Matiu and Makaro outspread, that sheltered us from war's alarms in other days; now are you lost to me. Mine eyes look upon the wayfarers lying yonder at Waitaha, but you, O sirs! O dames! by sad mischance are lost. Maybe you yet follow old familiar paths yonder at Porirua, but how indeed may I see you, O sirs ! Alas! Let my eyes roam vaguely to the scene of your wanderings at Arapaoa, though clearly seen by me you never more shall be, O Sirs ! O dames ! through yonder sea haze hanging low. Perchance you tread the way of Tuhirangi, he who tracks the canoe prow, lest ye astray should go from the water path at Te Aumiti. At what place are ye hidden from me, O sirs! Maybe within Tai-tawaro you are lost, the darkling depths concealing Tuhirangi, he who hither tracked the canoe of Kupe and Ngake to Aotearoa, when perished the Wheke of Muturangi at the barrier of Raukawa, hence Whatu-kaiponu and Whatu-tipare. And onward pressed to Te Aumiti that yawns agape, the point of vantage of the Koau-a-Toru, that, single winged, grips the assailing winds; but lost are you to me, O sirs ! Maybe in Whare-rau, at Waipuna, or stretch of sea past Pukerua, yon severed are from me.)

Notes:-

Waitaha. - There is a place of this name on the western shore of Lyall Bay.

Porirua. - The home of Kekerengu and his parents was at this place.

Arapaoa. - Ngati-Ira frequently crossed the Straits on visits to relatives living among the Sounds.

Tuhirangi is the native name of the famous Pelorus Jack of French Pass.

Te Aumiti. - The native name of the French Pass.

Tai-tawaro and Kaikai-a-waro are both names for the place where Pelorus Jack is said to have lived. He is credited, in Maori myth with having guided the canoe of Kupe hither from the isles of Polynesia.

Wheke a Muturangi. - A huge squid that, in another myth, Kupe is said to have followed, from Eastern Polynesia to this land. He killed it at The Brothers (Nga Whatu-kaiponu), which have been tapu ever since, and all people crossing the Straits had to veil their eyes when passing Nga Whatu, hence the expression whatu tipare, or veiled eyes.

Koau a Toru (or Potoru). Another myth concerning the voyager Kupe. See "Journal of the Polynesian Society," Vol. II, p. 147.

The crossing of Raukawa (Cook Straits) pp. 83-84

The sea of Raukawa, quoth Te Karehana Whakataki, of Porirua, to the writer twenty-five long years ago, is a tapu sea. In olden times those who crossed it for the first time might look neither to the right or left, nor yet behind. If one should break this rule, then the canoe was held stationary by supernatural powers for a day and night, only the most carefully conducted ritual of an expert could release it. All persons on a canoe carefully veiled their eyes with karaka leaves, lest they see the dread rocks of Nga Whatu, or Kapiti Island, which was also banned. When the shoal part of the Straits, away out in the middle, and called the tuahiwi was passed, the adept would call out - " O friends! Here is Takahi-parae," which is the name of the deep water on either side of the shoal. Then would the people rejoice at nearing the end of the voyage.

At one time the canoe of Tungia, father of Pirihana of Pukerua, was crossing Raukawa, when a man who did not believe in its mana ventured to look around. At once the canoe was held stationary by the Komako-huariki that guards the cod banks. As an adept named Te Rimurapa, of Kahungunu, was on board, they were able to proceed after a day's detention. The Komako-huariki is a small bird, and tapu; it is curiously marked and striped, unlike any ordinary bird. If heard by fishers on the banks, no fish will be caught.

Hori Ropiha, of Waipawa, stated that when a canoe crossed Raukawa from this island, Te Ika a Maui, to the South Island, Te Hei a Maui, all men, women and children had to cover their eyes. Also women expecting to become mothers were compelled to carefully cover their bodies, and the carved human figures at prow and stern of the canoe had to be covered likewise. This informant quotes a passage from an old song in proof of his statement:-

" Koparetia mai ko Te Whatu-kaiponu

Kei poua hoki koe, tahuri ki te moana."

To return to Ngati-Awa and their occupation of this district, there is little to add to the matter already published concerning their aggressive action towards the natives of Wai-rarapa, which finally compelled most of those folk to retire to Nuku-taurua, at Te Mahia, north of Hawkes Bay, leaving behind them a certain number to keep their fires burning on the land. Finally, after much fighting, the appearance of Europeans at Port Nicholson, seems to have had some effect towards putting a stop to hostilities, and shortly afterwards peace was concluded, and the refugees returned to Wai-rarapa.

In 1835 the strength of Ngati-Awa in this district was depleted by the removal of many of their fighting men to the Chatham Islands. These folk, having heard of the Chathams as being occupied by an unwarlike people, made up their minds to proceed thither. To this end they seized the brig ' Rodney,' then lying near Somes Island, and compelled the captain to take them down to the islands, where they soon made short work of most of the harmless natives. For an account of this raid and occupation see the " Journal of the Polynesian Society, Vol. I., p. 154.

The Maunga rongo or Peace making. pp. 84-

Finding themselves severely pressed by the new occupants of the Land of Tara, the clans of Wai-rarapa gradually withdrew to Nuku-taurua. This movement began after the death of the chief Te Maari-o-te-rangi (shot by Wi Tako at Te Roro, near Matakitaki, in Palliser Bay). One party, under Nuku, Te Rangi-takaiwaho and Tu-te-pakihi-rangi, a division of the Kahukura-awhitia clan, left from Te Iringa. On reaching Wai-marama, Nuku resolved to return and have another attempt to avenge the wrongs of his tribesmen. In one of the fights that ensued, Te Whare-pouri, a Ngati-Awa chief, managed to escape, but his wife, Te Ua-mai-rangi, and his daughter, Ripeka Te Kakapi-o-te-rangi, were captured by Nuku and his party, as also some others. This occurred at Tauwhare-rata. On arriving at Nga Umu-tawa, all the prisoners except Ripeka were released, and returned to their home at Pito-one by way of the coast. Nuku took Ripeka to Nuku-taurua, and gave her as a wife to one Ihaka. Then Nuku sent these two to the Harbour of Tara to propose a peace to Whare-pouri, hence the latter proceeded to Nuku-taurua, but, on his arrival there, found that Nuku had lately died. The task of peace making was then taken up by Tu-te-pakihi-rangi, who came down with a party and concluded the matter. After this the Wai-rarapa folk began to return to their homes, the bulk of them returning in 1842.

But several little unpleasantnesses occurred between the capture of Ripeka and the peace making. His party captured Tama-i-awhitia at Te Waipipi, and Tai-pa and Kai-toretore at Te Whangai, while Renata Kai-waewae was caught at Te Kai-kokirikiri, though Kokohi ransomed him for a musket named 'Rerepu.' When Nuku finally went north, he said to those of the Hamua and Ao-mataura clans who were remaining at Wai-rarapa, " Farewell! See that you keep my footsteps warm after I have departed. I go to follow the migrants of Wai-rarapa, but whatever fate may lie before us I will return, here to visit you." But Nuku, the fighter, was never again to look upon the vale of the Shining Water. He died in exile.

It was after this that Ngati-Tama, one of the clans holding the Harbour of Tara, under Te Kaeaea, Takotohau and Toheroa, raided Wai-rarapa and attacked and defeated the Kainga-ahi clan at Kopuaranga. This chief, Te Kaeaea, assumed the name of Taringa-kuri about this time, which came about in this wise: At a meeting of the loose confederation of northern tribes, Te Rangi-haeata of Ngati-Toa made a speech. One of Ngati-Awa asked the meaning of one of his remarks, which act angered Rangi, and he replied by an incisive utterance declaring that some of his dull witted hearers must have dogs ears (taringa kuri). Hence the Sparrow Hawk became Dog's Ear, and was so known from that time in his little hamlet at Kai-wharawhara.

The next act seems to have been a raid by the Hamua folk, who killed Te Pu-whakaawe at Waiwhetu, he being a sub-chief of Ngati-Awa. This seems to have occurred just about the time of the arrival of Tu-te-pakihi-rangi, who sent Ihaka Ngahiwi to Wai-rarapa to tell the people to stop fighting, as peace was being made. The following are the names of the persons who came to conclude peace with Ngati-Awa : -

| Peehi Tu-te-pakihi-rangi | Te Harawira |

| Hawaiki-rangi | Paora Kaiwhata |

| Kopa-kau | Tareahi |

| Tama-i-hikoia | Te Whawhao-po |

| Nga Tuere | Teira |

| Namana | Meihana Hapeta |

| Mikaere | Ihaka Motoro |

| Rihara | Raniera Roimata |

| Ngairo Te Apuroa | Ngariki |

| Te Rangi-takaiwaho | Whakataha |

| Piharau | Te Retimana |

| Kereopa | To Korou Mohaka |

| Pahoro Te Tio | Henare Te Mahukihuki |

| Kahu-tahei | Natanahira Te Nguha |

| Te Taatere |

It was arranged by Te Hapuku, Tareha and Te Moana-nui, and other chiefs that Te Whare-pouri, who was on a visit to Nuku-taurua, should remain there as a hostage during the sojourn of the above party in the district. This party seems to have been brought down the coast by some European vessel (kaipuke), the name of which is not given. When Peehi of the long name arrived here, the wife of Te Whare-pouri (Te Ua-mairangi) said to him : - " There is no property of Te Whare-poui here to serve as a gift to you, the only thing he left here is myself." On his return north, Peehi repeated this speech to Te Whare-pouri, who remarked; - "E pai ana, e taku hoa. He wai kowhao waka ma te tātā e tiehu, ahakoa wai tai, wai whenua ranei." (It is well, O friend. The leakage water of a canoe may be baled out with a scoop, whether it be salt water or fresh). And Te Ua was taken to wife by Peehi.

When the peace making was being discussed by the two peoples at the Hutt, Peehi made the following remarks in his speech to Honiana Te Puni, to Ngatata, to Kiri-kumara, to Miti-kakau, to Taringa-kuri, and the assembled peoples of Awa and other tribes: -

" List unto me, O ye peoples here assembled. I had given you no cause to come here and attack me and to take my land ; by you I was forced to drift away and dwell upon the lands of strangers. I was induced to proceed to the region occupied by the people whose weapon is the musket, then I returned here to meet you folk now before me. Well, yonder is Te Whare-pouri dwelling at Nuku-taurua, whither he went to induce his friend Nuku Te Moko-ta-hou to return to these parts. Now Nuku is dead, and here am I and the chiefs of Kahungunu assembled before you. Now we are looking at this new folk, the pakeha, and his characteristics. Who can tell whether he is kind and just to man? For his weapon is an evil weapon, and his intentions may also be evil.

This is my message to you : - I cannot occupy all the land. Yonder stands the great Tararua range, let the main range be as a shoulder for us. The gulches that descend on the western side, for you to drink the waters thereof - the gullies that descend on the eastern side, I will drink of their waters. Remain here as neighbours for me henceforward."

The offer of peace was accepted, both sides agreed thereto, with many, many speeches. The boundary betweed the two peoples ran from Turaki-rae along the main ridge to Remutaka, along that to Tararua, and on northward along its summit. And so the two peoples lived in peace on either side of that line, and knew not war, for the day of the white man had come, and the new ideas and productions of a strange race wrought a great change in the life of the Maori. The exiles at far away Nukutaurua returned south, many of them settling at Te Kopi-a-Uenuku, at Palliser Bay. The peace sought by the sons of Tara seven long centuries ago, when they settled on Miramar island, had come at last, and the memory wheels back to the song of Hau, the namer of names, he who sang:-

" Ka rarapa nga kanohi, e hine ! Ko Wai-rarapa,

Te rarapatanga o to tipuna." Etc., etc., etc.

The following anecdote was related to the writer by a Wai-rarapa native: - At one time a band of Ngati-Awa was returning from a raid on Wai-rarapa with prisoners. On arriving at a place near Orongorongo, one of the prisoners,Te Retimana, chanced to be walking just behind Te Wera, of the Mutnnga clan. Noting that no other members of the party were near, the prisoner offered to rearrange the strap of Te Wera's swag, under which straps was stuck a long handled tomahawk. As he did so he jerked the weapon out and delivered a blow at Te Wera, who, throwing up his hands as a guard, had both severely cut. Te Retimana killed him, fled up the hill into the bush, and escaped.

In these same wars one Pa-te-ika was captured at Hau-takere-waka. When the party reached Te Ngakau, at Te Kura-i-awarua, it was decided that the captive be killed. Pa accepted his fate after the manner Maori, merely asking permission to drink of the waters of the home stream hard by: - " Do not slay me until I have drank of the waters that flow past my home ! " Having done so, he stepped forth to receive his death blow, remarking as he did so : - "Aorangi tu noa, tāpākotinga takoto noa.'' And the next moment the old warrior passed out on the oldest of all trails, the Broad Way of Tāne that leads to the spirit world, to leave his final words to be treasured by his descendants.

One of the clans at Wai-rarapa that took part in these alarms and excursions was that known as Ngati-Parera, decendants of one Parera, who gained his name in a somewhat pecular way. A man named Te Au-hurihia escaped from a fray at Okakara clad merely in his birthday suit. Having made what a Texan would describe as his hot foot get-away, he espied a flock of ducks up the river, and managed to catch some of them. That night he lay out in the forest, and we are told that he retained warmth in his body by means of embracing the ducks. Hence he was given the name of Parera (duck), and he became the eponymic ancestor of the clans of that name.

The Wai-rarapa natives had a number of fortified villages as their principal places of residence in former times. Among them were the following: -

Pehikātia. Situated near Greytown. See "Maori History of the Taranaki Coast." p. 454.

Te Karearea. Situated at the mouth of the Otakoha stream Palliser Bay; on right bank.

Orongo-korero. At Cape Palliser.

Horewai. Situated just west of Whātārangi, Palliser Bay.

Tonganui-kaea, Situated at Kiriwai, N. W. side of Wai-rarapa lake. Said to have been a large place.

Heipipi. Opposite Kāhunui, on east side of Rua-mahanga river. Named after the old hill a at Petane (north of Napier). Occupied by the Hamua clan of Rangitane. An old saying was : - " Ko Rangi-tumau te maunga, ko Heipipi te pa"

Kakahi-makatea, Near Pounui lake or lagoon.

Nga Mahanga. On the Rua-mahanga river. The pa of Nuku.

Maunga-rake. At Wainuioru.

Oruhi. At mouth of the Whareama river

Te Iringa. An old Rangitane pa originally known as Ihu-toto. It was renamed by Nuku. Here it was that the Wai-rarapa natives assembled when the second party of Nga-Puhi raiders came down from the Napier district, instigated by Tiaki-tai in revenge for Para-rakau. The people gathered here because Tamahau had gained a reputation in his former fight with Nga-Puhi. Thirty of Nga-Puhi fell at Tawhanga, one of their chiefs, Tu Te Rangi-pokipoki, was slain by Tamahau with a spear. Some muskets were captured by Tamahau's force, one of which, named "Te Kiri o Te Peehi," is still preserved.

Tamawharu. A pa in the vicinity of Te Iringa.

Other old fortified places have already been mentioned in the narrative, and others appear in certain published works already alluded to, and in a paper on the chief Nuku, by Mr. T. W. Downes, for which see Vol. 45 of the "Transactions of the New Zealand Institute."

Rakai-ruru, the Taniwha. pp. 88

In former times, when the mana maori was extant, there abode in a small lake or lagoon, named Atua-hae, and situated near the northern end of Wai-rarapa lake, a fearsome taniwha, or demon, named Rakai-ruru. He was sometimes seen lying on the shore in the form of a log, which was not always ,of the same species of tree; it might be white pine at one time, and maire at another. When the river mouth is closed by shingle this demon resides at Atua-hae, but when the waters run free he goes for a jaunt to the South Island. When Europeans arrived in the district, Rakai resented their presence. Should anyone molest that log in any way it would disappear in a manner truly marvellous. Thus it is related of a gentleman of early days named Jack Murphy, presumably of Italian descent, that he attempted to split the demon log into posts. When he returned to his task next day, behold! the magic log had disappeared, leaving worthy Juan stranded on a logless shore.

It is highly probable that this story is quite true, inasmuch as it was told to the writer by an old resident of the district, a man who ought to know !

Ngati-Rangatahi at the Hutt. pp. 88

The clan of this name seems to have come from the Ohura district and to have settled in the upper part of the Heretaunga or Hutt valley. In their fighting against the Wai-rarapa natives they lost two chiefs and a number of commoners, whose bodies were eaten. Then the clan retired to Porirua and Kapiti. In 1842 these folk returned to the Hutt and commenced to dispute the settlers' claims to the land. These were the natives that gave so much trouble in that district, backed up as they were by Ngati-Toa of Porirua, Ngati-Rangatahi were related to Ngati-Tama.

Pito-One Pa. pp. 89

The Ngati-awa pa at Pito-one, where the chief Te Puni lived, is thus described in Hodder's "Memories of New Zealand Life": - "At the commencement of the Hutt Valley is a Maori pa, with divers strange whare (hut) and store rooms, fenced in with a double palisading of eight or ten feet high, and lashed with the native flax(?). Every three or four yards round the palisades are long posts, about a foot in diameter, ornamented with some grotesque carvings at the tops."

Echoes from other days. pp. 89

Some time after the Wai-mapihi fight, a raiding party from Wai-rarapa captured a woman named Te Wai-punahau at Waimea, near Wai-kanae. It was in order to regain this woman that Te Rangi-haeata, Te Hiko-o-te-rangi, Te Rangi-hiroa and Te Kanae made peace with the Kahungunu clans, when she was returned to her people. She is said to have been the mother of Wi Parata, whose father was a European named Stubbs. As a boy Wi Parata lived with a trader in the north. He lived at Tonga-porutu for some time, and then at Nga Motu with Te Atiawa, after which he came to Kapiti on a European ship. He is said to have witnessed the death of Tamaihara-nui, and to have lived at Te Awa-iti. He went to Port Cooper on a vessel that proceeded thence to Hobart Town, whereupon Wi went ashore and lived with Ngai-Tahu. In after years he was a well-known resident of Wai-kanae.

The bereaved mother of Puhirangi, an old-time legend of Miramar. pp. 89-91

The following is one of the best of the old songs pertaining to this district that has been collected. It is a lament by a woman named Te Ihu-nui-o-tonga for Rangi, her daughter, who had died. Te Ihu-nui was the wife of Tu-te-pewa-a-rangi, a chief of Puhirangi, a stockaded village that stood on the ridge above Karaka Bay. Prior to the death of the girl Rangi, the mother had been disturbed mentally by an omen of misfortune, the twitching of muscles or nerves termed tahakura and 10 tahae, hence she was apprehensive of coming misfortune, as expressed in the opening lines:-

Pa rawa, i, e te tahakura

E homai tohu ki au

Kia oho ake e te ngakau

Ko wai rawa koe e tahu nei i a au

Ka haramai e roto, ka kai kohau noa,

Ka waitohu noa

Tenei tonu i a koe, o te kahurangi

Ko wai rawa ka hua ko koe tonu, e Rangi, e !

Whatatai noa atu e te tinana

I a au ki roto o Puhirangi

E rauwiri noa mai ra a Hine.moana i waho

Tena ia koe ka riro i te au kume ki Tawhiti-nui

Ki Tawhiti-pamamao, ki Te Hono-i-wairua

I runga o Irihia.

Kia tika to haere ki roto o Hawaiki-rangi

E mau to ringa ki te toi huarewa

I kake ai Tane ki Tikitiki-o-rangi.

Kia urutomo koe ki roto o Te Rauroha

Kia powhiritia mai koe e nga mareikura

O roto o Rangiatea

Ka whakaoti te mahara i kona ki taiao

E hine . . e !(Omens assail me with signs that disturb the mind. Who indeed are you who thus afflicts me, and causes with vague warning a formless fear and questing mind ? It was indeed you, O cherished one. Who would have thought that you would go, O Rangi! Wearily inclines the body, as, within Puhirangi, I look forth on Hine-moana surging restlessly afar. But now you have gone, borne on the ocean stream to far Tawhiti-nui, Tawhiti-pamamao, to Te Hono-i-wairua on Irihia. Fare on, and carefully enter Hawaiki-rangi. Grasp in your hand the toi huarewa, the gyrating way by which Tane ascended to Tikitiki-o-rangi; that you may enter within Te Rauroha, that you maybe welcomed by celestial maids within Rangi-atea. Then shalt thou cease to remember this world, O maid!)

The picture here limned is that of the bereaved mother, sitting on the hilltop above Karaka Bay, surrounded by the dwellings of neolithic man, and gazing out over the defensive stockades to where the surging waves of Hine-moana, the serried ranks from the realm of Kiwa ever roll across the harbour mouth to attack the flanks of the Earth Mother. Then she farewells the spirit of her daughter, borne by the ocean currents along the ara whanui a Tāne, the broad way of Tane, the golden path of the setting sun, past Tawhiti-nui and Tawhiti-pamamao, the wayside resting places of her ancestors when they migrated from the hidden fatherland in the days when the world was young. To Te Hono-i-wairua on the sacred mountain in the great land of Irihia, the hot homeland of the Maori, where legions of dark skinned folk do dwell; to Hawaiki-rangi, wherein meet the spirits, of the dead, ere passing to the two spirit worlds. She then urges her child to ascend with care the whirlwind path by which Tāne of old ascended to the uppermost of the twelve heavens, to enter the precincts of Te Rauroha, a division of the uppermost of the heavens, and Rangiatea, the thrice tapu house or temple, there to be welcomed by the marei kura, female denizens of that realm, the realm of Io, the Supreme being, and where all thought and remembrance of this world would cease.

Herein we observe the mythopoetic fancies of uncultured man, of man who had not yet attained that stage of culture in which are involved the beliefs of punishments of the human soul after death, of raging fires and burning lakes, with other pleasing conditions invented by gentle priests.

Part V. Native place names of Wellington district (p. 92-)

Korero o te Wa I Raraunga I Rauemi I Te Whanganui a Tara I Whakapapa